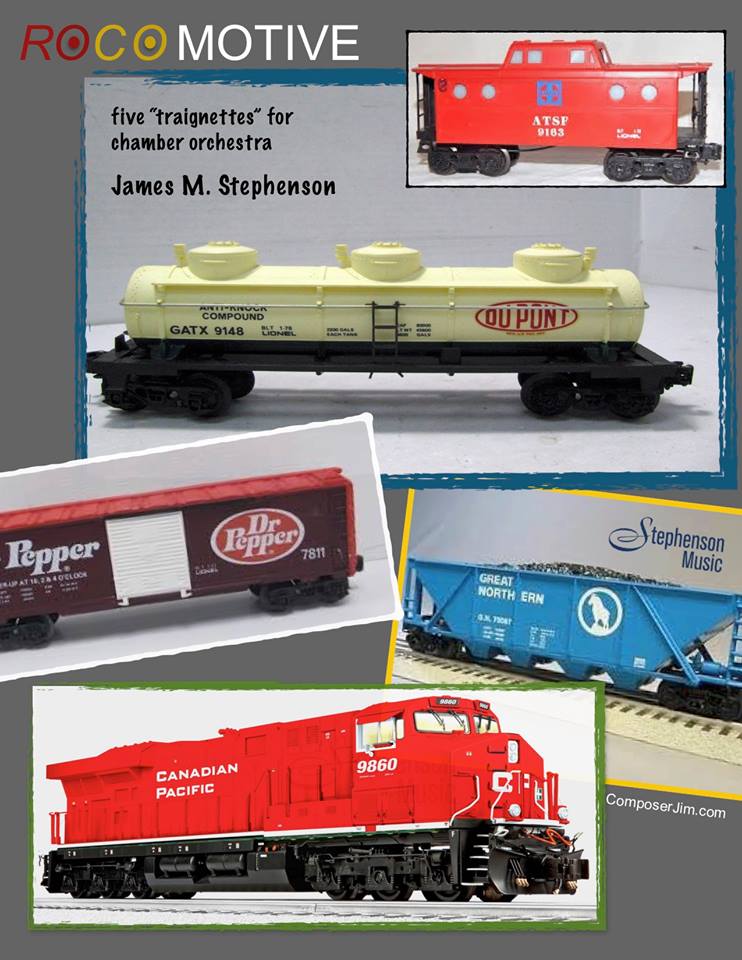

From orchestras, to bands, to choirs, plus soloists of almost every instrument – the music of composer Jim Stephenson has been performed by musicians of all ages, across America and the world. This weekend for ROCO In Concert: Ticket To Ride, we are thrilled to welcome him to Houston for the world premiere of his newest work celebrating the fun hobby of model railroading – ROCOmotive!

In this ROCOInsider, our Director of Marketing and Communications, Greta Rimpo, had a chance to catch up with Jim to learn more about the inspiration for this commission, how he unexpectedly fell into the business of composing, and the challenges of a busy career as an in-demand composer, conductor and arranger.

Hi Jim, thanks for chatting with me today! We are so looking forward to hearing ROCOmotive soon – what fun subject matter for a piece. How did the commission come about?

It all began when I met Alecia Lawyer many years ago at the St. Barts Music Festival which we both performed at, back when I was still playing trumpet professionally. I had known about ROCO even before that though and was impressed from afar at how open you are in approaching new music and how you engage with the audience, inviting them to “get in the kitchen with you” so to speak, to see how the music is created.

About 15 months ago, Alecia approached me in planning the season of “Games People Play” to be involved in a writing a piece, though at the time we weren’t sure what the piece would be about yet. As it got closer we discussed the idea of the work being about trains, which I was totally into – as I had distinct memories from childhood of my father designing a layout of Lionel trains, and all the many special tracks he had…even the smell of wood as he built a custom table for it.

How did you approach translating the character of a model train, into music?

Before I got started on the piece, I just knew that I needed to dig out my dad’s old train set for inspiration, to build it again, with my son .We gave it a try but could not get it up and running ourselves, so I called my dad over, he’s the expert! My son really got into the process – of how we would design the route, where to curve the track and to put the switchbacks, and with my dad’s help, we finally got it running. It was a lot of fun and gave me the idea to make each movement about a specific train car.

Before I got started on the piece, I just knew that I needed to dig out my dad’s old train set for inspiration, to build it again, with my son .We gave it a try but could not get it up and running ourselves, so I called my dad over, he’s the expert! My son really got into the process – of how we would design the route, where to curve the track and to put the switchbacks, and with my dad’s help, we finally got it running. It was a lot of fun and gave me the idea to make each movement about a specific train car.

There were about 10 cars on our train, but I knew I had to whittle it down to the 5 which gave me the most inspiration. I included the two most important first: the engine and the caboose. And from there, I chose the three with the most personality – the Dr. Pepper car, the coal hopper which was blue, and the oil tanker car.

After finishing a couple of heavy pieces this winter, my Symphony No. 3 and a bass trombone concerto for the Chicago Symphony, I saw this as a refreshing opportunity to write purely fun music. So, in essence, this is really a divertimento – music I hope is fun for both the orchestra and the audience.

So each movement personifies a rail car – what differentiates each of them musically?

I knew I wanted to use actual railroad tracks themselves as percussion instruments, so you’ll hear that a few times, plus what I call the “ROCOmotive” which takes the very distinct interval of a train whistle, a minor 7th chord, and is used in many ways throughout the piece to hold the whole thing together.

The first movement – dedicated to the first car of a train, the engine – gets things going with a minimalistic chugging rhythm, and the melody came from an interesting source. I had researched the companies who make these cars. Ours is made by Canadian Pacific Railway, which is mentioned in the original version of the 1888 folk tune “Drill, Ye Tarriers, Drill” – actually sung by workers while building the railroad.

The next movement is for the coal hopper car and this is our blues movement (as the car itself is a vibrant blue), where I take the ROCOmotive chord and break it up as the bass line. It’s probably my favorite of all – giving you a chance to just sit back, relax and chill out.

Then, we have the Dr. Pepper car – for this one I wrote ‘pop’ music (in the Midwestern sense of the word!) It’s the most lighthearted movement of all, and in fact, includes intervals paying homage to the Dr. Pepper commercial jingle of the late 1970s.

The shortest and fastest movement represents the oil tanker car, with the character of an oil slick – it’s virtuosic for the orchestra and features many small solos, especially in the woodwinds, I’m hoping they find it fun to play!

For the final movement – and the end of the train, the caboose – I did the opposite of what you might expect, it’s not a comical movement but rather a slow, beautiful piece to emphasize the importance of the caboose, and the work song melody comes back, but in reverse.

The main aim with ROCOmotive is: I want the performers and the audience to enjoy it, to feel it’s worth it to invest the time to play and listen to – but if someone were to study the score, they would see that it’s all here for a reason – every measure includes something meaningful, nothing by accident, and that’s in general what I do in my music.

It sounds like the process of writing happened quickly for this piece, and all at once – is that normal for you?

I don’t know how it is for other composers, but that’s how I work best – I know what the next piece is on the horizon, but I can’t think about it until I get there. I get so deep into the current piece I’m writing that I push future pieces out of my mind, though they keep spinning in my subconscious, which leads me to what I need to do to inspire myself to get going.

In this case, I knew I needed to build my dad’s model train, and I would see where that took me. One example – our train and tracks are so old now, from the 1950s, that when you flip the lever to make the train go, it makes this really ugly screech which actually became part of the piece. One of the first things you’ll hear is that very specific sound, made by a dissonant cello, bass, muted horn, and bassoon, before the engine starts chugging along.

Once a piece is written and being rehearsed, do you find sometimes you need to make edits, and why?

Oh yes, absolutely – mostly for balance. Every ensemble and acoustical environment is so unique. I might be imagining the last hall I was in instead of this hall, or a player may be different live, so on hearing it I may realize that say, I need to thin out the strings to hear a wind line better, etc. Also, because I used to be a player myself, I’m very sensitive to if something doesn’t feel right for a musician and am happy to make a change. I want my music to be a comfortable experience for everyone.

For example – in the virtuosic oil car movement of ROCOmotive, there was a bit I wanted to write for oboe, and I actually turned to Facebook to ask oboe players what they thought of it, how it felt – and they replied (including Alecia) to say that it felt awkward and maybe I should not do that. That was a great help and proved to be a big opportunity, as it changed other things I did in the piece too.

There is a hilarious story about how you fell into composing – involving a failed assignment to write “a bad piece of music!” Do you think you would ever have become a composer if not for that class?

In short – no! I was way too much of a trumpet nerd. When I was about 18, my parents threw this block party with all our friends there – and at that time my life was just all about the trumpet, all I wanted to talk about to people was that someday I was going to be principal trumpet in the Chicago Symphony!

Someone I was chatting with asked me if I had ever thought about composing, and I said, no, never – I had never even met a living composer. I thought being a composer was for dead people! And then only about six years later, I would end up writing my first piece, as a result of that summer class studying “bad music” at Northwestern University.

One person in that class said, “Wait, this isn’t bad – this is a cool piece!” What if they hadn’t? I don’t even know who that person was, but I wish I could thank them. It was that little spark I needed that got me started down this path, trying to write more and more “bad music” each day.

You attended Interlochen Arts Academy for most of high school, and New England Conservatory for college – what kind of classical music did you enjoy playing and listening to then? Any certain contemporary composers?

Interlochen had their own radio station, which would broadcast symphony orchestra concerts from around the country each night. I showed up with two boxes of rock and roll cassette tapes, like Journey, etc. – but I would actually put tape over the knockout tab on each cassette (really dating myself here!) so I could record over these tapes to hear every broadcast. I was just listening to and absorbing every bit of new repertoire I could. Then, in the orchestra at Interlochen, we performed a piece by Christopher Rouse, and that really made me take notice – I thought those were such cool sounds.

Another composer we played was Stephen Paulus, his Concerto for Orchestra, which had a wickedly hard trumpet part I wanted to nail. But the coolest thing was that he came to do a master class – that was the first time I met a composer who was alive, and that really made an impression, for me to see this young, living composer.

At New England Conservatory, I played in a couple of new music ensembles and brass quintet. Some student composers wrote stuff I didn’t want to play, and I could sense my colleagues didn’t want to either, so that definitely showed me what NOT to do. These reading sessions were hugely valuable for the composers too. One Saturday we did a session for orchestra – and I remember one composer practically crying because he had written this piece 10 years ago, and never had heard it live. I was shocked – I could not understand, then, why someone would write a piece with no hope of ever hearing it. Just shows how much I never thought I would become a composer. These experiences all informed how I work – I really want to write music that performers want to play and want to be a part of.

For 17 seasons, you played professionally with the Naples Philharmonic – and also got your start with arranging here, thanks to Pops conductor Erich Kunzel. How did that happen, and how important was his mentorship?

Erich was so busy conducting each weekend all over the world then – so, at each orchestra he visited, he needed a go-to arranger to create charts. At Naples I was really the only musician doing any kind of arranging, so a few colleagues recommended me, though I had only written two for brass quintet and never for orchestra!

He called me into his office and said, “I need ‘Here Comes Santa Claus’ for chorus and orchestra in December, go have some fun with it.” So I had to learn how to write for orchestra right then and there.

I was so proud, thinking I was so clever – I had turned it into a waltz, a tango, a jazz tune, and threw everything but the kitchen sink in one arrangement. Erich took me into his office, and said, “Jim – what are you thinking?!” He took his red pencil and scratched out half of it – letting me know what to do more of, what to do less of, and that’s how I learned. It was great. He was so smart, so quick.

Later, while rehearsing further arrangements, he would call me up so I could hear from the podium, to show me on the score while he was conducting what didn’t work – and he would have me conduct at times too, so I could see for myself. In those moments, I went from thinking I was pretty smart, to realizing how much I didn’t know in about five seconds.

As an arranger, you worked with a lot of popular artists and songs – often starting straight from the recording, doing what’s called a “lift” or “take-down,” with no sheet music. How did this process hone your ear, and inform your composing?

It trains you quickly and teaches a process to follow. First I would write the bass line, and the melody second – once you do that, the rest is a lot easier to fill in due to process of elimination, as you work out chords. Eventually, I got to where I could do a whole song in one day.

And still, that’s how I compose now – if I hear the bass line first I will sketch that, which informs the melody, and then the harmony – and I always orchestrate while I’m composing, as I go along.

I went through a period where I looked down on pop music, but when I was taking it apart every day to arrange, I began to realize why certain songs were so popular – what made a great groove, a catchy melody, or a cool chord progression, and this became part of my toolbox.

I think personally, at least in my composing, that classical music too needs some kind of hook just as much as pop music – we need that thing to grab the listener’s attention and keep them engaged, whether it’s a rhythm, or a tune or a character.

Once you got started composing, when did your first orchestra commission come along?

It was with the Naples Philharmonic in 1996, a piece called Legend of Sleepy Hollow, based on Washington Irving’s story. I had approached our conductor and management as we had a Halloween concert coming up, to see if they would let me write a piece for it. I had been composing for our brass quintet, so they said yes, and I really went to town, researching everything I could about Sleepy Hollow, New England folk tunes, and texts. It was a 20-minute piece for full orchestra with narrator – and I did it for just $500. I loved every minute of it.

After this I wrote an orchestral fanfare and a few other smaller works, then my first big commission was my Trumpet Concerto, and this was the first piece that gained me a wider recognition and was played a lot by others.

You also compose quite a bit for wind ensembles and bands – how did you get into that world?

One of my close friends from Interlochen became a band director himself – he thought my short piece, American Fanfare, would work well for band, so I arranged it for his group.

I think my score for it is still out of order in fact, because I didn’t even know the order of staves for a band score – as I had only ever played in or written for orchestra! But it worked out great and then one thing led to the next – now I’ve written and arranged a bunch of pieces for band, and that’s even where I’m headed to today, to work with an Iowa high school Honor Band on a new piece I’ve written for them.

In writing for younger players, how do you approach limitations they have? What challenges have you run into?

Basically, what I hope to do is to stay true to my style of writing, but just encapsulated in a different ensemble, with different rules. If I can’t write a high C for trumpet, then that’s fine – I can get creative and do other things.

I’ve also had to be more conscious about balance – I tend to write with an orchestral sound even for a wind group, more for one player on a part, and when you’re suddenly dealing with 5 tubas, 10 flutes etc., that can be a challenge.

I’m always learning still about what works when writing for young students. The most important part to me is that it’s an opportunity to connect with them, so they can interact with a living composer and hopefully, inspire their curiosity.

What is the toughest part of being a composer?

Self-doubt is a daily reality, I won’t lie – not just for composers but for most artists, it’s part of every day.

For example, I just wrote my 3rd Symphony which I’m really proud of (for the University of Miami Frost Symphony Orchestra) – it’s my biggest piece to date at 42-minutes and very serious music. Along the way I’m thinking, is anyone else ever going to play this again? Not because I don’t think it’s worth it but, it’s just so hard to get a new symphony played again, especially in the orchestral world.

Because look, when you’re going up against Brahms, Beethoven, or Tchaikovsky who wrote incredible symphonies – who am I to think that somebody should play mine on a program instead of theirs?

But then, just think about it this way – what if Beethoven, or Prokofiev, or Shostakovich had thought well, Haydn wrote 104 symphonies, why should I try to write any? But they did it anyway and shared with us their unique voices. So I have to just believe in what I’m writing, and hope there will be other ears out there who enjoy it and want to perform it, and that it will find its way into the repertoire.

What advice would you give to a young composer who feels discouraged, and is having trouble finding their own voice?

To write, to just do more of it. When I wrote my first piece, it was totally me just writing music based on other people’s music I heard, then with doing more of it, I realize that I need push myself to try something new that’s my own – and that’s how you can develop your voice, just by repetition.

I guarantee you – every single composer who’s considered standard these days has had fear, but also had that curiosity to keep trying and to want to make mistakes and learn from them.

I’ll be the same in the audience Saturday, wondering what works and what won’t, and I’ll learn from it, and that will inform the next piece I write.

What do you love most about composing? What drives you?

The curiosity. That’s what it all boils down to. No matter what I’m writing – it’s about that moment when it’s 3 am, and there’s nothing else I’d rather be doing, and I have that private secret with myself that I can’t wait for other people to find out about.

Just like any adventurer who gets to discover something first, then they get to share it with the rest of the world – that’s how I feel about composing a new piece, that’s what drives me.

And because I was also a performer – that moment of putting a piece of music on a fellow musician’s stand and hoping they really dig it, that they are going to enjoy playing it – I love that camaraderie.

I’m so happy the profession of composing found me on accident because I can’t imagine doing anything else now – and every day I’m still just pinching myself that I’m really doing it.

ROCO gives the world premiere of Jim Stephenson’s ROCOmotive – in ROCO In Concert: Ticket to Ride, Saturday, February 23, 2019, 5:00 pm, at The Church of St. John the Divine. Tickets available at roco.org, or at the door.

Leave A Reply